What might happen to mobile service in Greece should there be default against IMF, ECB, and debt

Photo credit European Press Agency

Just in case you are not up-to-date on the news, Greece is in big trouble. While its debt-to-GDP ratio is second only to Japan, the latter has a much larger economy that continues to grow. Unfortunately, decisions and actions taken over generations are finally catching up with Greece.

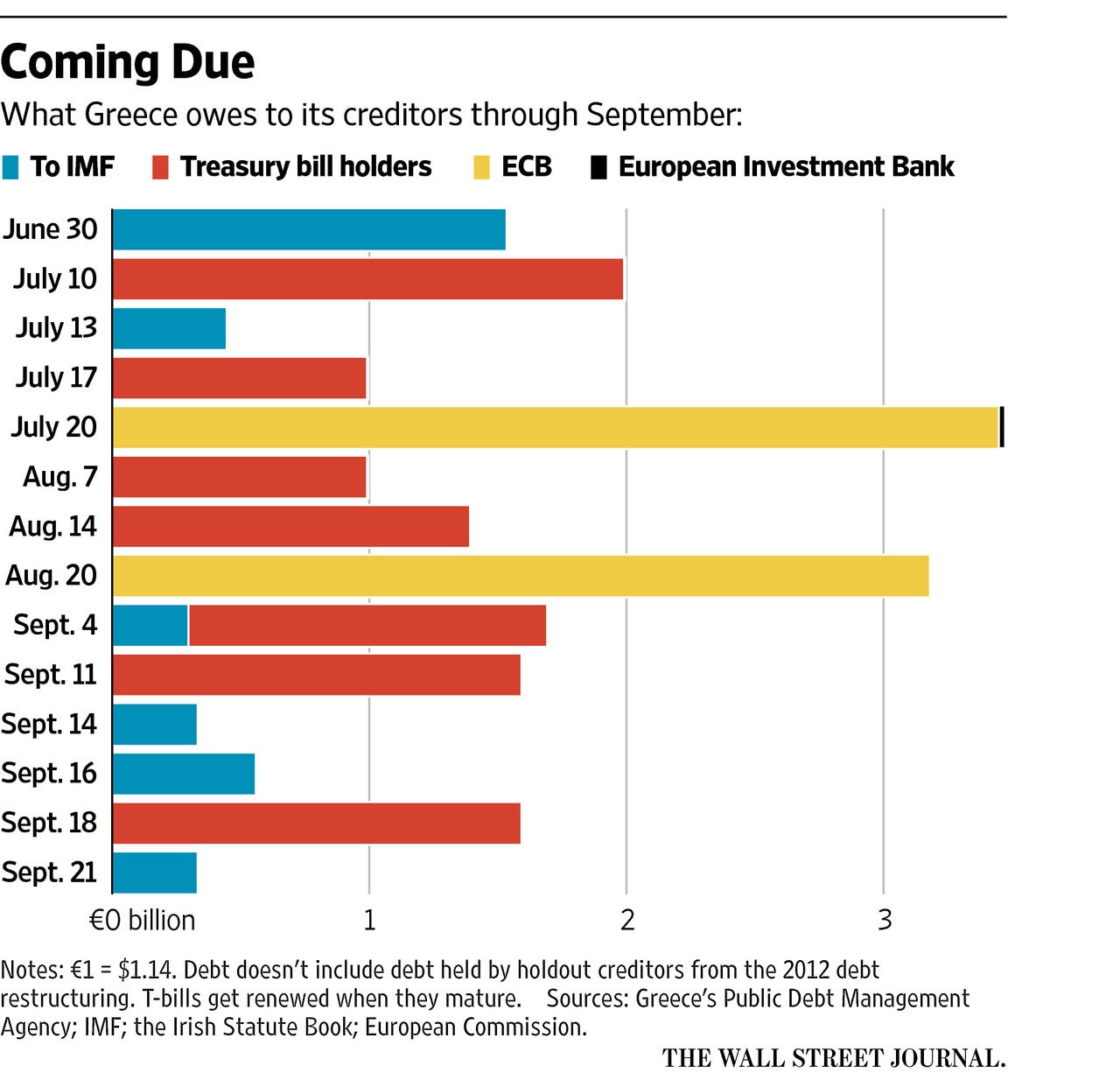

Late last week, last-minute arrangements were made for talks on Monday amongst the Greek government and European banking officials, including Germany, to see if any accommodation can be reached to keep the cash flowing through the Greek economy. To-date, the talks have not been going well, some of that may also be media hype, but the message is uniformly grim if Greece opts out of paying against its debts.

If that were to happen, what would be the fate of things that have become as natural to consumers’ lives as breathing, like wireless service? In the immediate term, nothing. However, in the short-term, it may be difficult to transfer funds to pay the bills if Greek banks put a choke hold on distributing monies that could potentially leave the country.

The carriers

Not accounting for Cyprus, Greece has three major mobile service providers, Cosmote, Vodafone, and Wind. Cosmote, with about 7.5 million subscribers, is a wholly owned subsidiary of OTE, the primary telecommunications company in Greece. OTE is 10% owned by the Greek government and 40% owned by Deutsche Telekom.

The three primary mobile providers in Greece

Finally, WIND Hellas is the third largest carrier in Greece, and ostensibly the most vulnerable in current economic climate. Creditors took over the company in 2010 and invested nearly half-a-billion euros to fund continued growth of the operation and contain debt. Despite those efforts, the mobile subscriber base has shrunk from over 4 million, 5 years ago, to a mix of mobile and wireline customers of the same number.

The crisis

Will Greece’s mobile and landline networks go dark if the country fails to come up with a plan? Not entirely, but the resulting constrictions on cash flow would ultimately have an impact on service. While no one is forecasting service to go down, it could very easily increase in price, dramatically.

The ripple effect is easy to follow. If you, the consumer, are limited in how much money can be withdrawn from your account for any reason, that obviously may be a factor in how you are able to pay the bill. If you cannot pay your bill, you lose service.

For Cosmote and Vodafone, their large, corporate parents will be able to weather most of the turbulence, but if a run on banks forces a freeze on assets or transfers of money, non-critical initiatives will be placed on hold, pared back to just keeping the lights (networks) on if necessary, until there is a decision to either get back in the good graces of the European Central Bank, or a decision for a “Grexit” from the euro currency altogether.

If there is a “Grexit”

There is little perceived upside if Greece were to leave the euro currency and return to the drachma (or whatever it would call its currency). Inflation would be an immediate concern, with on-going devaluations which means a mobile service bill will rise on two fronts, one being the devalued currency, and the other being on devalued assets coupled with increased costs to acquisition and maintenance.

Evi Pappa, an economics professor at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy, believes that if Greece manages to implement a new currency, devaluations will be frequent, and steep, at least 50% per adjustment. That means a basic plan on Vodafone Greece, normally €21.50 would cost in excess of 10,000GRD per month after just one devaluation adjustment.

Of course, this only addresses the cost of services. The same math can be applied to mobile devices as well. Those price tags will have a lot more zeros on them, inflated not only by devaluation, but also through value-added taxes (VAT) which are pervasive throughout Europe. Full retail on a new LG G4 on Vodafone Greece could cost more than 400,000GRD, a 16GB iPhone 6 would cost about the same (assuming some devaluation).

Nothing is certain

If there is anything we have learned over the past few years of the Euro-zone dealing with the Greek financial situation, it is that at least up to now, the money people on all sides have been able to avert serious problems with semi-last-minute arrangements.

However, the gaps between bankers, less debt-burdened countries of Northern Europe, and Greece, have been growing increasingly wider over the past couple of years. The formal meetings last week ended with people walking out saying that they were nowhere near reaching a solution.

Those that compare Greece’s circumstances to Argentina’s of a decade ago are overlooking that Argentina has its own currency, and before things started getting better, the banks were literally boarded-up with people banging on the doors with pots and pans.

For now, there will be another meeting on Monday. Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras and German Chancellor Angela Merkel will be the main figures, along with a cast of other ministers and bankers. Politically, there is positioning to see if one side or the other will blink on a given issue.

For the consumer, it means that basic staples of technology, which are a part of their daily lives, and have relatively low and stable price points under the euro, could become more difficult to pay for. If there is a “Grexit” from the euro, it will all become a lot more expensive in short order as well.

Things that are NOT allowed: